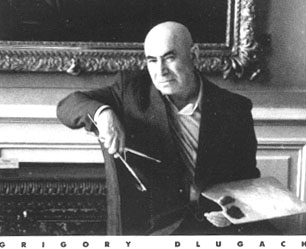

Dlugach entered the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts in the early 1930s. During his formative years, he experienced the strong influence of Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, for whom he retained feelings of deep veneration and gratitude for the rest of his life. It was owing to his interaction with that eminent artist that Dlugach came to regard the Hermitage Museum as the best possible school for pictoral mastery. During a Communist Party campaign waged against "formalism," Dlugach was made a victim of ideological aggression and had to leave the Academy without presenting his graduation picture. In the mid-1950s, he started working on his own in the Hermitage painting gallery where he developed a novel and original approach to art study based on the analytical interpretation of Old Masters' paintings.

Dlugach's stimulating experience, heightened as it was by the peculiar attraction of his unusual personality (reminiscent, to some extent, of Balzac's Maitre Frenhofer in "The Unknown Masterpiece"), proved most fascinating for several generations of young art students. It provided the basic principle for the work of the so called Hermitage School, a circle attended, at one time or another, by every member of the present Hermitage Group.

The reason why the practice of collective training was adopted, and carried on for several years, is not hard to guess. At a time when Art was made to repudiate real values in the name of formulas imposed upon it by official ideology, a painter refusing to I bow before it would naturally seek a way to escape from the realities of the situation, whether to the past or elsewhere. Added to this was a nostalgic yearning for genuine artistic culture, the quintessence of which was felt to be found in the treasures of the Hermitage collections. Here the greatest masters of world art stood for teachers. No form of hackwork, however ideologically welcome to the powers that be, had ever been admitted within these walls. The Museum remained sacred to Art, a temple spotless and unpolluted, state interference being confined to various instances of bureaucratic pressure. Here nothing stood between the Muse of Painting and her devotees.

Generally speaking, the Hermitage School may be described as based on Traditionalism. This tendency was strong enough to place the painters in opposition to the norms and canons of official art, on the one hand, and to the extremist trends in present vogue, on the other.

The primary goal of the School was to achieve artistic craftsmanship by mastering the secrets of the picture's plastic form. Gradually, however, the artists outgrew the limits of mere learning, and entered the field of research. This has been ably stated by Golovachov, one of the members of the Group: "In coming to the Hermitage, I was activated, in a large measure, by a purely practical motive, that is, the possibility of learning which it offered. But as time went on, the interest of learning was more and more superseded by that of investigation. You might argue that neither of these things can exist without the other. To this I would reply, with as much justification, that the two are by no means identical... It is the same as with the production of living cells in laboratory conditions: Nature has much better and simpler ways of doing this..."

Nothing could be farther from the spirit of the Group than Wagner's boast of "crystallizing" what Nature produced by organic methods:

'T

will be! the mass is working clearer!

Conviction gathers, truer, nearer!

The

mystery which for Man in Nature lies

We dare to test, by knowledge led;

And

that which she was wont to organize

We crystallize, instead.

Goethe, Faust, Part 2. Act 2

The Hermitage artists held, to the contrary, that Art was endowed with the same life-giving powers as Nature, viewed not as an object but as the subject of creation.

There is a lamentably long-lived tradition of disregarding the problem of form in art, an attitude from which stem all the commonplaces of rejecting "pure art," as if "impure" art could have any advantages over it! The very desire to understand the nature of artistic form has been condemned as well-nigh heretical. But what is Art if not a perfectly humanized form of Nature? Or does not a highly organized Rembrandt picture give one an insight into the Mystery of Life?

The problem of plastic form has always been at the center of the Group's interests. A specially trained power of perception("the art of seeing") is thought to be a prerequisite to its solution. Dlugach saw the essence of plastic form in Compactness; his favorite word for a picture possessing this quality was "a rock " He taught that supreme plastic unity was organic to works by such masters as Leonardo da Vinci, Veronese, Rubens, Poussin, Rembrandt, Van Dyck, Hals, Ruysdael, and other great artists down to Vrubel and Picasso. A willing mind may discern here a tendency to mythologize form; yet this is by no means in contrast to the nature of the creative process.

Basic to the structure of painting is a system of hidden lines: verticals, horizontals, diagonals, curves, etc. Invisible to the eye, they determine the degree of tension in the relation of a part to the whole. The representation has a plastic quality inasmuch as it possesses inner unity, each of its elements existing, and being perceived, in terms of its interrelation with the others and its degree of integration with them. The elements, whatever they may be, must have a certain pliancy of form, otherwise they could not possibly fit into the whole. This justifies the practice of Old Masters who made conscious use of distortion to integrate each part into the structure, making it subservient to the general effect. The stronger the tension in the part whole relation, the greater the power of expression achieved in a picture. That is what transforms a representation into an image. The plastic interpretation of form is akin to the poetic use of a word. It was not fortuitous that the most precise definition of plastic quality should have been given by a poet: Rilke, in one of his letters on the art of Cezanne, said that in his pictures each of the points seems to be aware of all the others.

The internal relations within the Hermitage Group varied, acquiring, at times, even a dramatic character. Not every painter could bring himself to stand "at the pedestals of Old Masters" forever. The experience of the Group gave rise to new branches and young shoots growing out from the main trunk. Free interpretation got the upper hand over analysis. This tendency was normal; sooner or later, each of the artists was bound to strike out on a path of his own. But, however widely the Hermitage tree might throw out its branches, the common cult of plastic values, shared by the painters, continued to link them in art as well as in life. Answers to the questions once asked of Old Masters were now sought by immediate observation of nature, mankind, and life.